The deposed queen of England Alditha fled to Ireland after the resistance to the Norman invasion led by her brothers Edwin and Morcar ended in their defeat. After Hastings in 1067 she gave birth to the deceased king’s son and named him Harold after his father. The infant travelled with her to Dublin around 1069/70 and both disappear from recorded history thereafter.

King Harold's mother, Gytha also held out against the Norman invaders and when William returned to Normandy, France in 1067, she fortified and held Exeter in Devon, the fourth largest city in the land. The Normans besieged the city in mid-winter and before it capitulated Gytha sailed with Harold's daughter Gytha and his sister, Gunnhild to the island of Flatholme in the Bristol Channel.

Harold’s sons Godwine and Edmund also fled to Ireland in the aftermath of Hastings and were hosted at the court of the king of Leinster Diarmait mac Maíl na mBó. In 1068 he supplied them with a fleet of 90 ships and they sailed to Bristol with a force of Dublin Norse mercenaries. They attempted to make Bristol their base but the locals resisted and they were forced to try and take it by force. Their resistance may have been due to a fear of drawing forth William's wrath. However, the city held and the brothers sailed off with plunder they had taken from the surrounding countryside. They came back the following summer to try and take Exeter but their army was heavily defeated and the two brothers returned to Dublin with the remnants. The failure of the Haroldsons to re-establish a base in England caused Gytha and the family with her on Flatholme to seek refuge with Count Baldwin VI of Flanders. Godwine and Edmund left Ireland and journeyed to the court of their cousin, King Swein of Denmark with the intention of enlisting his help to retake England. With Swein's death in 1074 all trace of the bothers was also lost to history.

Image: a panel from the Bayeux Tapestry depicting the death of the King of England after he was shot with an arrow through his eye. These days the entire tapestry can be viewed at Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux, Normandie, France. It is worth a visit.

Thursday, November 7, 2013

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Halloween, its Irish roots

As millions of children and adults prepare to participate in the fun of Halloween on the night of October 31st, few will be aware of its ancient Celtic roots in the Samain or in modern Irish Samhain (p. S-owin) festival. In Celtic Ireland about 2,000 years ago, Samhain was the division of the year between the lighter half (summer) and the darker half (winter). At Samhain the division between this world and the otherworld (world of the dead) was at its thinnest, allowing spirits to pass through. Samhain occurs on Nov 1st and was one of the great fire festivals, it marked the start of the Celtic new year.

On the eve of Samhain families invited the spirits of their ancestors home and honoured them whilst harmful spirits were warded off. Evil spirits would search the world of the living looking for souls to carry back with them to the otherworld. The best defence against the evil spirits was to pretend to be one and thus the evil ones would pass one over and continue searching for a victim (i.e. someone not in costume! You have been warned). So began the modern Halloween tradition of dressing in scary costumes. A tradition dating back millennia and brought by Irish emigrants firstly to Scotland and later to North America and now the four corners of the Earth.

Bonfires and food played a large part in the festivities. The bones of slaughtered livestock were cast into a communal fire, household fires were extinguished and started again from the bonfire. (This is where the term "Bone fire" originates) The ritual symbolises the death of the old year and the birth of the new.

Food was prepared for the living and the dead. As the dead were in no position it eat it, it was ritually shared with the less well off.

Christianity incorporated the honouring of the dead into the Christian calendar with All Saints (All Hallows) on November 1st, followed by All Souls on November 2nd. The wearing of costumes and masks to ward off harmful spirits survived as Halloween customs. The Irish emigrated to America in great numbers during the 19th century especially around the time of famine during the 1840's. The Irish carried their Halloween traditions to America, where today it is one of the major holidays of the year.

Through time other traditions have blended into Halloween, for example the American harvest time tradition of carving pumpkins has travelled back across the atlantic. Originally the Irish made Jack-o'-lanterns out of turnips or beet but nowadays pumpkins are much easier to carve.

Two hills in the Boyne Valley were associated with Samhain in Celtic Ireland, Tlachtga and Tara. Tlachtga was the location of the Great Fire Festival which begun on the eve of Samhain (Halloween). Tara was also associated with Samhain, however it was secondary to Tlachtga in this respect.

We call it a Celtic festival because Samhain is a Celtic word but the celebration of Samhain is pre-Celtic. The entrance passage to the Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara is aligned with the rising sun around Samhain. The Mound is 4,500 to 5,000 years old, suggesting that Samhain was celebrated long before Celtic culture arrived in Ireland about 2,500 years ago.

A traditional Irish turnip Jack-o'-lantern dating from the early 20th century is on display in the Museum of Country Life, in Castlebar, Co. Mayo. If you are not easily scared you can have a look at a picture of it here!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Traditional_Irish_halloween_Jack-o%27-lantern.jpg

Image: modern celebrations of Samhain at Tlachtga (Hill of Ward) near Athboy, Co Meath is 12 miles from the Hill of Tara. The earthworks which are about 150 metres in diameter are most impressive from the air. Tlachtga dates from approximately 200 AD and was the location of the Great Fire Festival begun on the eve of Samhain (eve of the 1st November).

On the eve of Samhain families invited the spirits of their ancestors home and honoured them whilst harmful spirits were warded off. Evil spirits would search the world of the living looking for souls to carry back with them to the otherworld. The best defence against the evil spirits was to pretend to be one and thus the evil ones would pass one over and continue searching for a victim (i.e. someone not in costume! You have been warned). So began the modern Halloween tradition of dressing in scary costumes. A tradition dating back millennia and brought by Irish emigrants firstly to Scotland and later to North America and now the four corners of the Earth.

Bonfires and food played a large part in the festivities. The bones of slaughtered livestock were cast into a communal fire, household fires were extinguished and started again from the bonfire. (This is where the term "Bone fire" originates) The ritual symbolises the death of the old year and the birth of the new.

Food was prepared for the living and the dead. As the dead were in no position it eat it, it was ritually shared with the less well off.

Christianity incorporated the honouring of the dead into the Christian calendar with All Saints (All Hallows) on November 1st, followed by All Souls on November 2nd. The wearing of costumes and masks to ward off harmful spirits survived as Halloween customs. The Irish emigrated to America in great numbers during the 19th century especially around the time of famine during the 1840's. The Irish carried their Halloween traditions to America, where today it is one of the major holidays of the year.

Through time other traditions have blended into Halloween, for example the American harvest time tradition of carving pumpkins has travelled back across the atlantic. Originally the Irish made Jack-o'-lanterns out of turnips or beet but nowadays pumpkins are much easier to carve.

Two hills in the Boyne Valley were associated with Samhain in Celtic Ireland, Tlachtga and Tara. Tlachtga was the location of the Great Fire Festival which begun on the eve of Samhain (Halloween). Tara was also associated with Samhain, however it was secondary to Tlachtga in this respect.

We call it a Celtic festival because Samhain is a Celtic word but the celebration of Samhain is pre-Celtic. The entrance passage to the Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara is aligned with the rising sun around Samhain. The Mound is 4,500 to 5,000 years old, suggesting that Samhain was celebrated long before Celtic culture arrived in Ireland about 2,500 years ago.

A traditional Irish turnip Jack-o'-lantern dating from the early 20th century is on display in the Museum of Country Life, in Castlebar, Co. Mayo. If you are not easily scared you can have a look at a picture of it here!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Traditional_Irish_halloween_Jack-o%27-lantern.jpg

Image: modern celebrations of Samhain at Tlachtga (Hill of Ward) near Athboy, Co Meath is 12 miles from the Hill of Tara. The earthworks which are about 150 metres in diameter are most impressive from the air. Tlachtga dates from approximately 200 AD and was the location of the Great Fire Festival begun on the eve of Samhain (eve of the 1st November).

Monday, September 9, 2013

Polygamy & Divorce in ancient Ireland

Old Irish law tracts give pride of place to a man’s one official wife, the "first in the household" (cetmuinter), who normally contributed movable property of her own to the joint housekeeping and was entitled to receive it back, with any accumulated profits, if the couple divorced later.

Divorce could be initiated by either the husband or the wife, on a number of grounds. A wife, for example could cite her husband’s impotence or sterility, beating her severely enough to leave a scar, homosexuality causing him to neglect her marriage bed, failure to provide for her support, discussing her sexual performance in public, spreading rumours about her, his having tricked her into marriage by using magic arts, or his having abandoned her for another woman. In this last case, however, the first wife had the right to remain in the marriage if she wished, and was then entitled to continued maintenance from her husband.

Image: A protest with style! Fashion Model and cultural activist Constance Buccafurri dressed as the Celtic goddess Eriu holding the Book of Kells to protest at the proposal to build a motorway close the the world heritage site of Newgrange, Co. Meath.

The goddess Eriu or Éire (p. aer ah) gave her name to the land most know as Ireland. Foreigners not knowing how to pronounce the accent over the first 'é' and the correct pronunciation of last e ( 'ah') will pronounce the word Éire as "ire" hence Ire-land or Éireland!

Divorce could be initiated by either the husband or the wife, on a number of grounds. A wife, for example could cite her husband’s impotence or sterility, beating her severely enough to leave a scar, homosexuality causing him to neglect her marriage bed, failure to provide for her support, discussing her sexual performance in public, spreading rumours about her, his having tricked her into marriage by using magic arts, or his having abandoned her for another woman. In this last case, however, the first wife had the right to remain in the marriage if she wished, and was then entitled to continued maintenance from her husband.

Image: A protest with style! Fashion Model and cultural activist Constance Buccafurri dressed as the Celtic goddess Eriu holding the Book of Kells to protest at the proposal to build a motorway close the the world heritage site of Newgrange, Co. Meath.

The goddess Eriu or Éire (p. aer ah) gave her name to the land most know as Ireland. Foreigners not knowing how to pronounce the accent over the first 'é' and the correct pronunciation of last e ( 'ah') will pronounce the word Éire as "ire" hence Ire-land or Éireland!

Monday, August 5, 2013

Scot means Irish

The Book of Armagh declares the High King of Ireland, Brian Boru to be “Imperator Scottorum” or “Emperor of the Irish”. Ireland was named by the Romans “Scotia” and its people Scoti. The invasion of Irish tribes of northern Britain led it acquiring the name “Scotland” or land of the Irish.

A 9th century philosophiser working on the continent writes his name as Johannes Scotus Eriugena - John the Irishman born in Ireland (Ériu-gena/born) as opposed to Scotland. Almost three centuries before Isadore of Seville wrote that Ireland and Scotland were the same country. Later the lands were distinguished as Scotia Major (Ireland) and Scotia Minor (Scotland). Hibernia is also a Roman term for the Island of Ireland and can be translated as “the land of eternal winter” or “wintry”. It is sometimes claimed that the name Hibernia derives from the ancient Greek name for the island Iouernía an alteration of the Q-Celtic name Iweriu. A variant Ierne was also used; Claudian 395 AD says “When the Scots put all Ireland in motion (against the Romans), then over heaps of Scots the Icy Ierne wept”. In other words many Irish were killed when they attacked the Romans in Britain. In 391 AD a Roman Consul, Quintus Aurelius Symmachus received a present of seven "canes Scotici" or Irish wolfhounds.

An article on the author Thomas Dempster (1579-1625) in the Dictionary of National Biography remarks of his book that it 'is chiefly remarkable for its extraordinary dishonesty', claiming as Scots not only almost all Irish men of any renown but also Alcuin, Boniface and even Boadicea.

Thomas Dempster's fraudulent claims are illustrative of the confusion caused by the Roman word for an Irish person "a Scot" After the Norman invasion the exonym "Ireland" increased in popularity and the old distinction between Scotia major (Ireland) and Scotia minor (Scotland) was lost and many a poor scholar since have assumed erroneously that Scot means a person from Scotland! The confusion allowed the Scots to steal much of Irish history and claim it as their own.

Even the pope was a victim of the Scottish whitewash when in 1577 he handed over control of Regensburg, Schottenkloster, the oldest and most illustrious of the Irish foundations in Germany to Scottish monks on the grounds that it had been an originally a Scottish foundation which had been subsequently taken over by the Irish. The Scot element in Schottenkloster no doubt influenced his decision.

Ireland, the Land of Saints and Scholars sent so many missions to the continent that people there held the term "scottus" as synonymous with 'saint'. All those meanings are now lost to all but astute students of history and followers of Irish Medieval History on Facebook!

An Irish man, a saint and a scholar known to history as St. Donatus of Fiesole (Italy) wrote a poem about his homeland in the 9th century. Note Scotland was never and Island!

Far westward lies an isle of ancient fame,

By nature bless'd; and Scotia is her name,

Enroll'd in books: exhaustless is her store,

Of veiny silver, and of golden ore.

Her fruitful soil, for ever teems with wealth,

With gems her waters, and her air with health;

Her verdant fields with milk and honey flow;

Her woolly fleeces vie with virgin snow;

Her waving furrows float with bearded corn;

And arms and arts her envied sons adorn!

No savage bear, with lawless fury roves,

Nor fiercer lion, through her peaceful groves;

No poison there infects, no scaly snake

Creeps through the grass, nor frog annoys the lake;

An island worthy of its pious race,

In war triumphant, and unmatch'd in peace!

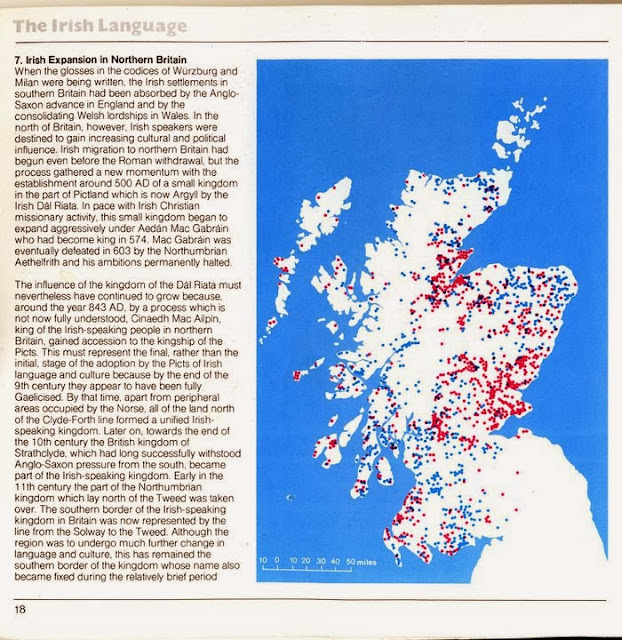

Image: distribution map of Irish place names in Scotland.

A 9th century philosophiser working on the continent writes his name as Johannes Scotus Eriugena - John the Irishman born in Ireland (Ériu-gena/born) as opposed to Scotland. Almost three centuries before Isadore of Seville wrote that Ireland and Scotland were the same country. Later the lands were distinguished as Scotia Major (Ireland) and Scotia Minor (Scotland). Hibernia is also a Roman term for the Island of Ireland and can be translated as “the land of eternal winter” or “wintry”. It is sometimes claimed that the name Hibernia derives from the ancient Greek name for the island Iouernía an alteration of the Q-Celtic name Iweriu. A variant Ierne was also used; Claudian 395 AD says “When the Scots put all Ireland in motion (against the Romans), then over heaps of Scots the Icy Ierne wept”. In other words many Irish were killed when they attacked the Romans in Britain. In 391 AD a Roman Consul, Quintus Aurelius Symmachus received a present of seven "canes Scotici" or Irish wolfhounds.

An article on the author Thomas Dempster (1579-1625) in the Dictionary of National Biography remarks of his book that it 'is chiefly remarkable for its extraordinary dishonesty', claiming as Scots not only almost all Irish men of any renown but also Alcuin, Boniface and even Boadicea.

Thomas Dempster's fraudulent claims are illustrative of the confusion caused by the Roman word for an Irish person "a Scot" After the Norman invasion the exonym "Ireland" increased in popularity and the old distinction between Scotia major (Ireland) and Scotia minor (Scotland) was lost and many a poor scholar since have assumed erroneously that Scot means a person from Scotland! The confusion allowed the Scots to steal much of Irish history and claim it as their own.

Even the pope was a victim of the Scottish whitewash when in 1577 he handed over control of Regensburg, Schottenkloster, the oldest and most illustrious of the Irish foundations in Germany to Scottish monks on the grounds that it had been an originally a Scottish foundation which had been subsequently taken over by the Irish. The Scot element in Schottenkloster no doubt influenced his decision.

Ireland, the Land of Saints and Scholars sent so many missions to the continent that people there held the term "scottus" as synonymous with 'saint'. All those meanings are now lost to all but astute students of history and followers of Irish Medieval History on Facebook!

An Irish man, a saint and a scholar known to history as St. Donatus of Fiesole (Italy) wrote a poem about his homeland in the 9th century. Note Scotland was never and Island!

Far westward lies an isle of ancient fame,

By nature bless'd; and Scotia is her name,

Enroll'd in books: exhaustless is her store,

Of veiny silver, and of golden ore.

Her fruitful soil, for ever teems with wealth,

With gems her waters, and her air with health;

Her verdant fields with milk and honey flow;

Her woolly fleeces vie with virgin snow;

Her waving furrows float with bearded corn;

And arms and arts her envied sons adorn!

No savage bear, with lawless fury roves,

Nor fiercer lion, through her peaceful groves;

No poison there infects, no scaly snake

Creeps through the grass, nor frog annoys the lake;

An island worthy of its pious race,

In war triumphant, and unmatch'd in peace!

Image: distribution map of Irish place names in Scotland.

Wednesday, July 10, 2013

Ancient hospitals - foras tuaithe.

Over a thousand years before Florence Nightingale and health insurance or national health service the ancient Irish had laws dictating hygiene standards for hospitals and persons unable to pay for their treatment were treated free of charge paid for by the community. This sets Ireland apart from the rest of Europe which too had hospitals but only for the élite except in times of war when ordinary men could be treated for war wounds in field hospitals.

Early hospitals were secular and were for the use of the people of the area and were called "foras tuaithe" or ‘House of the territory. These were distinct from monastic hospitals which came into being later.

Water, cleanliness and ventilation were the three main requirements for the foras tuaithe and it had to have four doors open, one to the north, to the south, to the east and to the west ‘so that the invalid may be seen from every side. Water was to be in the form of a stream running through the middle of the floor. The care of the sick could also be carried out in private houses but water, cleanliness and ventilation were still a requirement. The treatment of a sick man could not be carried out in the house of the man who injured him, in a place where the sick man was revolted by its dirty condition or in a place where the sick man felt further injury may be done to him.

People who could afford to pay for treatment were expected to pay but if unable to do so there was a levy put on the district to cover the cost. If the person’s illness/injury was caused by another then that person was liable for all the costs of treatment and maintenance. The Bretha Crólige (Binchy, 1938), a law tract which has been placed in the first half of the eight century gives detailed requirements about the obligations regarding maintenance of the sick and compensation in the event of injury. The cost of maintenance and fees due to the liaig is also carefully laid down. Some people were not allowed be brought away on sick maintenance i.e. a young girl before the age of consent and an old man over the age of eighty eight. In these instances food and treatment had to be brought to their place of abode. The text also tells us that there are three errors in nursing; the error of leaving the victim without food, the error of leaving him without the liaig, and the error of leaving him without a substitute. The problems associated with the latter, namely loss of income is also mentioned in this tract

‘There are seven sick maintenances most difficult to support in Irish law [in the territory]: maintenance of a king, maintenance of a hospitaller, maintenance of a poet , maintenance of an artificer, maintenance of a smith, maintenance of a wise man, maintenance of an embroideress. For it is necessary [to get] somebody to undertake their duties in their stead so that the earnings of each of them may not be lacking in his house’

Boys between the ages of fourteen and twenty were accompanied by their mother and she also stayed with her child if she was still breastfeeding.

Every patient was to be fed according to the directions of the liaig and the basic fare was two properly baked loaves of bread every day plus different condiments depending on the rank of the patient. Unlimited celery was given to patients of every social rank due to its healing properties and garlic was also recommended. Honey is approved of in one part of the text and forbidden in another section. Fish or flesh cured with sea salt and horse salt were generally forbidden but not to the noble grades who were allowed it every day from New Years Eve to the beginning of Lent and then twice a week during the summer.

Fresh meat was to be given to every one but how often is not clarified. Boys and girls between the ages of seven and ten were entitled to the fare they would receive while in fosterage. The Bretha Crólige gives the legal requirements of treatment but not the details of the therapeutic regime. It is highly unlikely that garlic was given to everyone without question as garlic would be injurious to those of choleric temperament (O’Cuin, 1415). There were also many leper hospitals but these were generally connected with the monasteries and such institutions until they were suppressed under Henry VIII.

Extracted from "An overview of the Irish Herbal Tradition. The Thread that could not be Broken" By Rosari Kingston

Image: A modern foras tuaithe - Cork Medical Centre, Cork, Ireland.

Early hospitals were secular and were for the use of the people of the area and were called "foras tuaithe" or ‘House of the territory. These were distinct from monastic hospitals which came into being later.

Water, cleanliness and ventilation were the three main requirements for the foras tuaithe and it had to have four doors open, one to the north, to the south, to the east and to the west ‘so that the invalid may be seen from every side. Water was to be in the form of a stream running through the middle of the floor. The care of the sick could also be carried out in private houses but water, cleanliness and ventilation were still a requirement. The treatment of a sick man could not be carried out in the house of the man who injured him, in a place where the sick man was revolted by its dirty condition or in a place where the sick man felt further injury may be done to him.

People who could afford to pay for treatment were expected to pay but if unable to do so there was a levy put on the district to cover the cost. If the person’s illness/injury was caused by another then that person was liable for all the costs of treatment and maintenance. The Bretha Crólige (Binchy, 1938), a law tract which has been placed in the first half of the eight century gives detailed requirements about the obligations regarding maintenance of the sick and compensation in the event of injury. The cost of maintenance and fees due to the liaig is also carefully laid down. Some people were not allowed be brought away on sick maintenance i.e. a young girl before the age of consent and an old man over the age of eighty eight. In these instances food and treatment had to be brought to their place of abode. The text also tells us that there are three errors in nursing; the error of leaving the victim without food, the error of leaving him without the liaig, and the error of leaving him without a substitute. The problems associated with the latter, namely loss of income is also mentioned in this tract

‘There are seven sick maintenances most difficult to support in Irish law [in the territory]: maintenance of a king, maintenance of a hospitaller, maintenance of a poet , maintenance of an artificer, maintenance of a smith, maintenance of a wise man, maintenance of an embroideress. For it is necessary [to get] somebody to undertake their duties in their stead so that the earnings of each of them may not be lacking in his house’

Boys between the ages of fourteen and twenty were accompanied by their mother and she also stayed with her child if she was still breastfeeding.

Every patient was to be fed according to the directions of the liaig and the basic fare was two properly baked loaves of bread every day plus different condiments depending on the rank of the patient. Unlimited celery was given to patients of every social rank due to its healing properties and garlic was also recommended. Honey is approved of in one part of the text and forbidden in another section. Fish or flesh cured with sea salt and horse salt were generally forbidden but not to the noble grades who were allowed it every day from New Years Eve to the beginning of Lent and then twice a week during the summer.

Fresh meat was to be given to every one but how often is not clarified. Boys and girls between the ages of seven and ten were entitled to the fare they would receive while in fosterage. The Bretha Crólige gives the legal requirements of treatment but not the details of the therapeutic regime. It is highly unlikely that garlic was given to everyone without question as garlic would be injurious to those of choleric temperament (O’Cuin, 1415). There were also many leper hospitals but these were generally connected with the monasteries and such institutions until they were suppressed under Henry VIII.

Extracted from "An overview of the Irish Herbal Tradition. The Thread that could not be Broken" By Rosari Kingston

Image: A modern foras tuaithe - Cork Medical Centre, Cork, Ireland.

Saturday, June 1, 2013

Healing with music

40% of the ancient metal horns which survive in the world are Irish! The island of Ireland is particularly noted for its great collection of ancient musical instruments. Spanning more than 3000 years from the Late Stone Age through to the Early Medieval Period (4200BC – 1000AD), they reflect the evolvement of many changes in Irish culture. Great feats of bronze casting and sheet metal work were achieved to produce fine practical instruments of musical and visual excellence.

The exceptionally large numbers of Irish metal horns which survive clearly indicates the importance which was placed on music in ancient Ireland. Yet, similar finds in lesser numbers in Britain and Western Europe also place ancient Ireland in an important International context. The earliest Irish legends contain many references to instruments and music being played in a variety of situations.

Ancient Ireland had Music therapy! Legend tells us of a young prince Fraoch who was severely wounded by a bite from giant Eel (possibly the progenitor of the Loch Ness monster). The wounded Fraoch was stretchered into a chamber led by seven trumpeters playing a special magic healing music that was so powerful that 30 of Queen Medb`s courtiers died upon hearing it.

The website of Music Therapy Ireland states - "the 20th century discipline began after World War I and World War II, when community musicians, both amateur and professional, went to hospitals around the country to play for the thousands of veterans suffering from both physical and emotional trauma from the wars. The patients’ notable physical and emotional responses to music led the doctors and nurses to request the hiring of musicians by the hospitals. It was soon evident that the hospital musicians needed some prior training before entering the facility and so the demand grew for a college curriculum."

Horns produce of sound on a variety of frequencies including inaudible ultrasound. Modern science tells us that there are three primary benefits to ultrasound as a medical treatment. The first is the speeding up of the healing process from the increase in blood flow in the treated area. The second is the decrease in pain from the reduction of swelling and edema. The third is the gentle massage of muscles tendons and/ or ligaments in the treated area because no strain is added and any scar tissue is softened. These three benefits are achieved by two main effects of therapeutic ultrasound. The two types of effects are: thermal and non thermal effects. Thermal effects are due to the absorption of the sound waves. Non thermal effects are from cavitation, microstreaming and acoustic streaming

Conditions which ultrasound may be used for treatment include the follow examples: Ligament Sprains, Muscle Strains, Tendonitis, Joint Inflammation, Plantar fasciitis, Metatarsalgia, Facet Irritation, Impingement syndrome, Bursitis, Rheumatoid arthritis, Osteoarthritis, and Scar Tissue Adhesion.

You can hear the ancient horns of Ireland on the Ancient Music Ireland (Ceol Ársa na hÉireann) website performed by Simon O'Dwyer and Maria Cullen O'Dwyer, who are based in Connemara in the West of Ireland. (Look for the video at the bottom of the page.) Spiritual healing may still come from musicians but these-days medical healing is best left to physicians! Enjoy.

http://www.prehistoricmusic.com/

The exceptionally large numbers of Irish metal horns which survive clearly indicates the importance which was placed on music in ancient Ireland. Yet, similar finds in lesser numbers in Britain and Western Europe also place ancient Ireland in an important International context. The earliest Irish legends contain many references to instruments and music being played in a variety of situations.

Ancient Ireland had Music therapy! Legend tells us of a young prince Fraoch who was severely wounded by a bite from giant Eel (possibly the progenitor of the Loch Ness monster). The wounded Fraoch was stretchered into a chamber led by seven trumpeters playing a special magic healing music that was so powerful that 30 of Queen Medb`s courtiers died upon hearing it.

The website of Music Therapy Ireland states - "the 20th century discipline began after World War I and World War II, when community musicians, both amateur and professional, went to hospitals around the country to play for the thousands of veterans suffering from both physical and emotional trauma from the wars. The patients’ notable physical and emotional responses to music led the doctors and nurses to request the hiring of musicians by the hospitals. It was soon evident that the hospital musicians needed some prior training before entering the facility and so the demand grew for a college curriculum."

Horns produce of sound on a variety of frequencies including inaudible ultrasound. Modern science tells us that there are three primary benefits to ultrasound as a medical treatment. The first is the speeding up of the healing process from the increase in blood flow in the treated area. The second is the decrease in pain from the reduction of swelling and edema. The third is the gentle massage of muscles tendons and/ or ligaments in the treated area because no strain is added and any scar tissue is softened. These three benefits are achieved by two main effects of therapeutic ultrasound. The two types of effects are: thermal and non thermal effects. Thermal effects are due to the absorption of the sound waves. Non thermal effects are from cavitation, microstreaming and acoustic streaming

Conditions which ultrasound may be used for treatment include the follow examples: Ligament Sprains, Muscle Strains, Tendonitis, Joint Inflammation, Plantar fasciitis, Metatarsalgia, Facet Irritation, Impingement syndrome, Bursitis, Rheumatoid arthritis, Osteoarthritis, and Scar Tissue Adhesion.

You can hear the ancient horns of Ireland on the Ancient Music Ireland (Ceol Ársa na hÉireann) website performed by Simon O'Dwyer and Maria Cullen O'Dwyer, who are based in Connemara in the West of Ireland. (Look for the video at the bottom of the page.) Spiritual healing may still come from musicians but these-days medical healing is best left to physicians! Enjoy.

http://www.prehistoricmusic.com/

Thursday, May 30, 2013

Irish Female Family Names

Female Gaelic surnames differ from male

surnames because girls & women could not be a son or grandson!

Accordingly, Ó (from Ua meaning grandson of) is replaced with Ní and Mac

(meaning son of) is replaced with Nic. These are contractions of the original form of the female surnames "Iníon Uí" and "Iníon Mhic" (modern O and Mac). The naming system worked like this

The forename is placed first and is followed by "Iníon Uí" which in turn is followed by her great Grandfathers name for example -Iníon Uí Donaill - meaning daughter of the grandson of Donal. Where Mac is used the original form was "Iníon Mhic" meaning the daughter of the son of (name) for example Máire Iníon Mhic Donaill translates as Mary daughter of the son of Donal

When women married they dropped the ní and nic and took the title "Bean" (p. ban) meaning wife for example Bean Uí Dhónaill or Bean Mhic Gearailt.

Obviously surnames could change with each generation but there is evidence to suggest that surnames were becoming fixed (like those of today) before the Norman Invasion. According to Fr. Woulfe, an early authority on Irish surnames, the first recorded fixed surname is O'Clery (Ó Cleirigh), as noted by the Annals, which record the death of Tigherneach Ua Cleirigh, lord of Aidhne in Co. Galway in the year 916. It seems likely that this is the oldest surname recorded anywhere in Europe.

The forename is placed first and is followed by "Iníon Uí" which in turn is followed by her great Grandfathers name for example -Iníon Uí Donaill - meaning daughter of the grandson of Donal. Where Mac is used the original form was "Iníon Mhic" meaning the daughter of the son of (name) for example Máire Iníon Mhic Donaill translates as Mary daughter of the son of Donal

When women married they dropped the ní and nic and took the title "Bean" (p. ban) meaning wife for example Bean Uí Dhónaill or Bean Mhic Gearailt.

Obviously surnames could change with each generation but there is evidence to suggest that surnames were becoming fixed (like those of today) before the Norman Invasion. According to Fr. Woulfe, an early authority on Irish surnames, the first recorded fixed surname is O'Clery (Ó Cleirigh), as noted by the Annals, which record the death of Tigherneach Ua Cleirigh, lord of Aidhne in Co. Galway in the year 916. It seems likely that this is the oldest surname recorded anywhere in Europe.

Thursday, May 23, 2013

Fairy Rings

Fairy beliefs - practically every article

written on the subject of fairies suggests that people once believed in

them. It is true to say that people would avoid certain actions for fear

of tempting fate rather than actually believing in fairies.

The modern world of science has similar parallels for example one of

the world’s most popular sports, Formula 1 is purely based on science,

mathematics and engineering. It is also a dangerous sport and there is

no number 13 and it is not that people actually believe that 13 is bad

luck but why should one tempt fate and add to the already high risk

nature of the sport? (Cars did carry the number 13 until a spate of

fatal accidents occurred in the 1920s to drivers with number 13,

prompting the French automobile club to stop using the number and the

tradition remains to this day.)

Fairy rings also occupy a prominent place in European folklore as the location of gateways into elfin kingdoms or places where elves gather and dance. According to the folklore, a fairy ring appears when a fairy, pixie, or elf appears. The circular pattern of the mushrooms looks like a place where fairies danced in a ring holding hands.

In an Irish legend recorded by Jane Wilde (mother of Oscar), a farmer built a barn on a fairy ring despite the protests of his neighbours. He was struck senseless one night and a local "fairy doctor" was called to break the curse. The farmer says that he dreamed that he must destroy the barn. - No doubt this particular variety of mushroom was hallucinogenic!

Collecting dew from the grass or flowers from inside a fairy ring can bring bad luck. While destroying a fairy ring is both unlucky and fruitless as it will just grow back. Also science tells us some mushrooms in fairy rings are poisonous and inhaling mushroom spores can cause a respiratory disease called Lycoperdonosis.

Moonshine distillers traditionally discard the first 50ml of distillate known sometimes as the fairy portion. Science tells us that the first few drops from a still contain nasty and unwanted substances like methanol which have a lower boiling point than alcohol and therefore come out of the still first.

Therefore we can conclude that some superstitions were useful in learning scientific knowledge.

Image: A fairy ring on a suburban lawn in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

Fairy rings also occupy a prominent place in European folklore as the location of gateways into elfin kingdoms or places where elves gather and dance. According to the folklore, a fairy ring appears when a fairy, pixie, or elf appears. The circular pattern of the mushrooms looks like a place where fairies danced in a ring holding hands.

In an Irish legend recorded by Jane Wilde (mother of Oscar), a farmer built a barn on a fairy ring despite the protests of his neighbours. He was struck senseless one night and a local "fairy doctor" was called to break the curse. The farmer says that he dreamed that he must destroy the barn. - No doubt this particular variety of mushroom was hallucinogenic!

Collecting dew from the grass or flowers from inside a fairy ring can bring bad luck. While destroying a fairy ring is both unlucky and fruitless as it will just grow back. Also science tells us some mushrooms in fairy rings are poisonous and inhaling mushroom spores can cause a respiratory disease called Lycoperdonosis.

Moonshine distillers traditionally discard the first 50ml of distillate known sometimes as the fairy portion. Science tells us that the first few drops from a still contain nasty and unwanted substances like methanol which have a lower boiling point than alcohol and therefore come out of the still first.

Therefore we can conclude that some superstitions were useful in learning scientific knowledge.

Image: A fairy ring on a suburban lawn in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Making Irish surnames English

In 1518 a City

Council decreed “neither O' nor Mac shall strut and swagger through the

streets of Galway”. The names of the native Irish male population all

began with O’ or Mac meaning “grandson of” or “son of”

followed by the personal name of the ancestor. In the late 16th century

the Irish nation under duress began the process of changing their

surnames to be more English sounding.

The English Poet Edmund Spencer who spent 20 years in Ireland called upon the English to commit genocide against the Irish as Earl Arthur Grey had done in 1582 using brutal scorched earth tactics resulting in a serious famine which killed as many as 30,000 people in just six months.

The Elizabethan conquest of Ireland resulted in the establishment of a central government in Ireland for the first time, the outlawing of the native Brehon laws and imposition of English law, the ethnic cleansing of the native population, the despising of Irish manner hairstyles, clothing and all things Gaelic. Therefore it is not surprising that it became unfashionable to have an Irish name.

While the surname change process was initiated by oppression it was not simply due to it alone but was driven by a complex interplay of many different circumstances. For example one could gain significant social advantages by appearing to be English or to appear to be in support of the English. Families might even be able to avoid land confiscations. However written records do not allow us to count the many families went by their original name but used an official name for paper records and interactions with government. (perhaps this is the primary reason for the survival of Irish surnames). A similar practice continues to this day most notably in the forename Liam, almost no holder of this name is called Liam on their birth certificate. They are all called William.

English officials unfamiliar with the Irish language recorded surnames as the heard them and thus wrote the names down a phonetically. For example Mag Oireachtaig (Ma-gur-ach-ti) becomes Ma’Geraghty or Mac Geraghty. Another scribe might hear it different like Mc Garrity or recorded it carelessly. Thus one surname takes on the appearance of many and we get all these variations Gerrity, Gerty, Gerighty, Gerighaty, Gerety, Gerahty, Garraty, Geraty, Jerety, McGerity, MacGeraghty, MacGartie, MacGarty and many more.

Misspellings were also common because the uniformity of spelling we enjoy today was not present in the English language until very recently. An interesting example is William Shakespeare (1564-1616) who spelled his name in a variety of ways. Despite his great learning and literary accomplishments 83 variants of his name have been attested in English source material

Direct translations of Irish names also occurs for example Ó Marcaigh to Ryder, Ó Bradáin to Salmon and Fisher, Mac an tSaoir to Carpenter or Freeman , Mac Conraoi to King, Ó Draighneáin (meaning from a place abounding in briars) is translated to Thornton. Ó Gaoithín (meaning from a windy place) is translated to Wyndham.

Assimilation is the name given to the process of substitution with foreign names of similar sound or meaning like these French examples. Ó Lapáin became De Lapp, Ó Maoláin became De Moleyns, Ó Duibhdhíorma became D'Ermott. Molloy (O’ Maol an Mhuaidh) and Mulligan (O’Maoláin) became Molyneux.

Pure substitution occurs where the connection between the original surname and the substitute is remote for example, Clifford for Ó Clúmháin, Fenton for Ó Fiannachta, Loftus for Ó Lachtnáin, Neville for Ó Niadh, Newcombe for Ó Niadhóg.

Sometimes rare names are often subsumed by more common names in a process called attraction.

Ó Bláthmhaic is anglicised as Blawick or Blowick and becomes Blake

Ó Braoin is anglicised as O'Breen, Breen becomes O'Brien,

Ó Duibhdhíorma is anglicised as O'Dughierma or Dooyearma, becomes MacDermott,

Ó hEochagáin is anglicised as O'Hoghegan becomes Mageoghegan,

Ó Maoil Sheachlainn is anglicised as O'Melaghlin becomes MacLoughlin.

Image taken from “Mapping the Emerald Isle: a geo-genealogy of Irish surnames”. Tip: type in a name of interest or zoom to a place to see the names associated with that place in 1890.

http://storymaps.esri.com/stories/ireland/

The English Poet Edmund Spencer who spent 20 years in Ireland called upon the English to commit genocide against the Irish as Earl Arthur Grey had done in 1582 using brutal scorched earth tactics resulting in a serious famine which killed as many as 30,000 people in just six months.

The Elizabethan conquest of Ireland resulted in the establishment of a central government in Ireland for the first time, the outlawing of the native Brehon laws and imposition of English law, the ethnic cleansing of the native population, the despising of Irish manner hairstyles, clothing and all things Gaelic. Therefore it is not surprising that it became unfashionable to have an Irish name.

While the surname change process was initiated by oppression it was not simply due to it alone but was driven by a complex interplay of many different circumstances. For example one could gain significant social advantages by appearing to be English or to appear to be in support of the English. Families might even be able to avoid land confiscations. However written records do not allow us to count the many families went by their original name but used an official name for paper records and interactions with government. (perhaps this is the primary reason for the survival of Irish surnames). A similar practice continues to this day most notably in the forename Liam, almost no holder of this name is called Liam on their birth certificate. They are all called William.

English officials unfamiliar with the Irish language recorded surnames as the heard them and thus wrote the names down a phonetically. For example Mag Oireachtaig (Ma-gur-ach-ti) becomes Ma’Geraghty or Mac Geraghty. Another scribe might hear it different like Mc Garrity or recorded it carelessly. Thus one surname takes on the appearance of many and we get all these variations Gerrity, Gerty, Gerighty, Gerighaty, Gerety, Gerahty, Garraty, Geraty, Jerety, McGerity, MacGeraghty, MacGartie, MacGarty and many more.

Misspellings were also common because the uniformity of spelling we enjoy today was not present in the English language until very recently. An interesting example is William Shakespeare (1564-1616) who spelled his name in a variety of ways. Despite his great learning and literary accomplishments 83 variants of his name have been attested in English source material

Direct translations of Irish names also occurs for example Ó Marcaigh to Ryder, Ó Bradáin to Salmon and Fisher, Mac an tSaoir to Carpenter or Freeman , Mac Conraoi to King, Ó Draighneáin (meaning from a place abounding in briars) is translated to Thornton. Ó Gaoithín (meaning from a windy place) is translated to Wyndham.

Assimilation is the name given to the process of substitution with foreign names of similar sound or meaning like these French examples. Ó Lapáin became De Lapp, Ó Maoláin became De Moleyns, Ó Duibhdhíorma became D'Ermott. Molloy (O’ Maol an Mhuaidh) and Mulligan (O’Maoláin) became Molyneux.

Pure substitution occurs where the connection between the original surname and the substitute is remote for example, Clifford for Ó Clúmháin, Fenton for Ó Fiannachta, Loftus for Ó Lachtnáin, Neville for Ó Niadh, Newcombe for Ó Niadhóg.

Sometimes rare names are often subsumed by more common names in a process called attraction.

Ó Bláthmhaic is anglicised as Blawick or Blowick and becomes Blake

Ó Braoin is anglicised as O'Breen, Breen becomes O'Brien,

Ó Duibhdhíorma is anglicised as O'Dughierma or Dooyearma, becomes MacDermott,

Ó hEochagáin is anglicised as O'Hoghegan becomes Mageoghegan,

Ó Maoil Sheachlainn is anglicised as O'Melaghlin becomes MacLoughlin.

Image taken from “Mapping the Emerald Isle: a geo-genealogy of Irish surnames”. Tip: type in a name of interest or zoom to a place to see the names associated with that place in 1890.

http://storymaps.esri.com/stories/ireland/

Thursday, May 9, 2013

The Two Patricks et al

St. Patrick was not Irish, St George was not

English, St Andrew was not Scottish and of the four nations only the

Welsh St. David is a native patron saint. St. Patrick was not Welsh or

English as it is sometimes claimed in error because Wales

and England did not exist in Patrick’s time. He was a Romano-Briton

meaning of a Roman family living in Roman colonial Britain prior to the

withdrawal of the Romans.

St George never killed a Dragon and St. Patrick never banished snakes from Ireland and some claim he did not even bring Christianity to Ireland it was Palladius. Therefore the Irish should be celebrating St. Palladius Day on March 17th which is and absurdity reliant on gross ignorance of plain Latin for sustenance!

The great Irish historian T. F. O'Rahilly's "Two Patricks" theory first posited in a lecture in 1942 where he decided to be deliberately controversial in order the initiate academic debate. O'Rahilly like many scholars before noted that a continental chronicler wrote that Palladius was ordained bishop by the pope and sent to Ireland in AD431. Yet tradition tells us that Patrick was ordained bishop and sent to Ireland to convert the Irish in AD432. O'Rahilly was arguing correctly that the histories of two men had been confused and folded together in error. No official record exists of Palladius or Patrick’s ordination and the issues arising from the debate has been the subject of much speculation. However, it is not possible to say much about Palladius due to the lack of evidence other than one thing; it is certain that he did not bring Christianity to Ireland and this is expressly stated in the historical record.

Prosper of Aquitaine states in a chronicle entry for the year ad431 “Ad Scotum in Christum credentes ordinatur a Papa Celestino Palladius et primus episcopus mittitur”.

Translated as “To the Irish believing in Christ Pope Celestine sends Palladius as the first Bishop”.

In plain black and white is the statement that there were Christians in Ireland before Palladius arrived and by extension before the arrival of Patrick too!

St George never killed a Dragon and St. Patrick never banished snakes from Ireland and some claim he did not even bring Christianity to Ireland it was Palladius. Therefore the Irish should be celebrating St. Palladius Day on March 17th which is and absurdity reliant on gross ignorance of plain Latin for sustenance!

The great Irish historian T. F. O'Rahilly's "Two Patricks" theory first posited in a lecture in 1942 where he decided to be deliberately controversial in order the initiate academic debate. O'Rahilly like many scholars before noted that a continental chronicler wrote that Palladius was ordained bishop by the pope and sent to Ireland in AD431. Yet tradition tells us that Patrick was ordained bishop and sent to Ireland to convert the Irish in AD432. O'Rahilly was arguing correctly that the histories of two men had been confused and folded together in error. No official record exists of Palladius or Patrick’s ordination and the issues arising from the debate has been the subject of much speculation. However, it is not possible to say much about Palladius due to the lack of evidence other than one thing; it is certain that he did not bring Christianity to Ireland and this is expressly stated in the historical record.

Prosper of Aquitaine states in a chronicle entry for the year ad431 “Ad Scotum in Christum credentes ordinatur a Papa Celestino Palladius et primus episcopus mittitur”.

Translated as “To the Irish believing in Christ Pope Celestine sends Palladius as the first Bishop”.

In plain black and white is the statement that there were Christians in Ireland before Palladius arrived and by extension before the arrival of Patrick too!

Thursday, May 2, 2013

The Noble Hound

In early Irish society dogs were considered

noble creatures possessing aspiring qualities like intelligence,

loyalty, companionship, guardianship, speed and agility, the very human

qualities imperative for survival in all early societies especially

for warriors. Heroes in both real life and mythology were given names

with “dog” or more specifically “hound” in the title like Cú Chulainn,

Con Cétchathach etc. The evidence of reverence of our ancestors had for

these creatures is abundant in surnames and sometimes in place names

like Connacht, Connemara, Conaghrea. Glenamaddy, Limivaddy etc. However,

most of the place names ultimately derive from personal names.

Con, (the genitive form of Cú) depending on the context in which it is found can translate directly as wolf/dog/hound but its original sense would be more akin to hero, great warrior or tribal leader. Con is sometimes anglicised with an extra ‘n’ e.g. Conn.

Many Irish names which begin with Cú (a hound) were originally all prefixed with Mac with apparently one exception, which took the O’, namely, Cú-cheanann, which gave rise to the surname O Conceanainn, anglicised 'Concannon,' and sometimes even 'Cannon possibly meaning ‘fairheadded hound/hero’'.

Sometimes Con means wolf as in Conalty which comes from O’Conallta meaning wild wolf. The Irish for wolf hound is Faolchú Faol- cú - wild hound. Other names for a wolf include mac tire and madra alla/allta (wild dog).

Madra is the word for dog in modern Irish and is found in the surnames Madden, MacAvaddy, Madigan from O’Madaihín and Mac a' Mhadaidh. This form is found in place names too like Limavaddy (Leim an mhadaidh) literally “the dog's leap”.

Glenamaddy from Gleann na Madadh" Gleann meaning valley and madhadh from madra meaning dog. This would suggest that the name means "Valley of the Dogs".

Some other examples of names with ‘con’; Conboy from Conbhuidhe meaning yellow (haired) hound/hero. Conneely from Mac Conghalile, the gal element means valour thus valorous hero. Connolly has the same meaning but it derives from the Munster O’Conghalile.

Conway (Mac Con-bhuadha, sometimes also for Mac Con-mhaighe) Conmee, or Conmey (Mac Con-Midhe - hound of Meath), Confrey (Mac Confraoich – hound of the heather), Conroy (Mac Con-raoi- warrior king).

Some names have retained the Mac and suppressed the Con; but have put in a syllable 'na,' which does not occur in the original Irish form such as Macnamee (for MacConMidhe –hound of meath), Macnamara (for Mac Con-mara - Cú-mara - sea-hound). It is also found with the words swapped around as in Murchú often anglicised as Murphy which also translates a hound of the Sea. MacCon - Mac Mhíolchon meaning hunting dog.

Image: Fionn Mac Cumhaill accompanied by his two hounds, Bran and Sceolan located near Newbridge, Co. Kildare at Exit 12 of M7 motorway.

Con, (the genitive form of Cú) depending on the context in which it is found can translate directly as wolf/dog/hound but its original sense would be more akin to hero, great warrior or tribal leader. Con is sometimes anglicised with an extra ‘n’ e.g. Conn.

Many Irish names which begin with Cú (a hound) were originally all prefixed with Mac with apparently one exception, which took the O’, namely, Cú-cheanann, which gave rise to the surname O Conceanainn, anglicised 'Concannon,' and sometimes even 'Cannon possibly meaning ‘fairheadded hound/hero’'.

Sometimes Con means wolf as in Conalty which comes from O’Conallta meaning wild wolf. The Irish for wolf hound is Faolchú Faol- cú - wild hound. Other names for a wolf include mac tire and madra alla/allta (wild dog).

Madra is the word for dog in modern Irish and is found in the surnames Madden, MacAvaddy, Madigan from O’Madaihín and Mac a' Mhadaidh. This form is found in place names too like Limavaddy (Leim an mhadaidh) literally “the dog's leap”.

Glenamaddy from Gleann na Madadh" Gleann meaning valley and madhadh from madra meaning dog. This would suggest that the name means "Valley of the Dogs".

Some other examples of names with ‘con’; Conboy from Conbhuidhe meaning yellow (haired) hound/hero. Conneely from Mac Conghalile, the gal element means valour thus valorous hero. Connolly has the same meaning but it derives from the Munster O’Conghalile.

Conway (Mac Con-bhuadha, sometimes also for Mac Con-mhaighe) Conmee, or Conmey (Mac Con-Midhe - hound of Meath), Confrey (Mac Confraoich – hound of the heather), Conroy (Mac Con-raoi- warrior king).

Some names have retained the Mac and suppressed the Con; but have put in a syllable 'na,' which does not occur in the original Irish form such as Macnamee (for MacConMidhe –hound of meath), Macnamara (for Mac Con-mara - Cú-mara - sea-hound). It is also found with the words swapped around as in Murchú often anglicised as Murphy which also translates a hound of the Sea. MacCon - Mac Mhíolchon meaning hunting dog.

Image: Fionn Mac Cumhaill accompanied by his two hounds, Bran and Sceolan located near Newbridge, Co. Kildare at Exit 12 of M7 motorway.

Thursday, April 25, 2013

Animals in river names.

Celtic peoples held

lakes and rivers to be sacred as evinced from their mythology. According

to the myths the rivers Shannon and the Boyne were created by

goddesses. The sacred nature of water is also evident in the

archaeological record due to the many finds of votive offerings of

precious objects in watery places. Sometimes river names reveal creation

myths not by gods but by furrowing animals. It may be indicative of how

sacred these animals were once considered.

The pig was one such animal, spending its lifetime furrowing through the earth creating river like meandering channels. It gives its name of the River Suck in Connacht which is one of the main tributaries of the River Shannon. The word derives from the old Irish word for pig ‘socc’ or more specifically the pigs digging instrument the snout. The river, Afon Soch and the village named after it Abersoch in Wales contain the element ‘soch’ which is of Celtic origin and thus related to the Irish word ‘socc’.

In Wales also there is the river Twrch (literally 'hog') in Ystalyfera and Llanuwchllyn are other examples, as is the river Hwch (sow) near Llanberis. Banw, a word for a 'piglet', is apparent in the river names Banw in Montgomeryshire and the rivers Aman (from Amanw) and Ogwen.

Image: River Suck at O’Flynn’s Lock C. Roscommon.

The pig was one such animal, spending its lifetime furrowing through the earth creating river like meandering channels. It gives its name of the River Suck in Connacht which is one of the main tributaries of the River Shannon. The word derives from the old Irish word for pig ‘socc’ or more specifically the pigs digging instrument the snout. The river, Afon Soch and the village named after it Abersoch in Wales contain the element ‘soch’ which is of Celtic origin and thus related to the Irish word ‘socc’.

In Wales also there is the river Twrch (literally 'hog') in Ystalyfera and Llanuwchllyn are other examples, as is the river Hwch (sow) near Llanberis. Banw, a word for a 'piglet', is apparent in the river names Banw in Montgomeryshire and the rivers Aman (from Amanw) and Ogwen.

Image: River Suck at O’Flynn’s Lock C. Roscommon.

Thursday, April 18, 2013

Early Medieval Ireland and advanced engineering

The oldest tidal mill so far discovered in the world

belongs to Monastery of Nendrum on Mahee Island on Strangford Lough in

Co. Down.The first tidal mill was constructed there between 619 and

621AD making it older than the previously earliest known tidal mill at

Little Island in Co. Cork which dates from about 630AD. The Cork mill is

a A twin flume horizontal-wheeled tide mill.

The oldest tidal mill so far discovered in the world

belongs to Monastery of Nendrum on Mahee Island on Strangford Lough in

Co. Down.The first tidal mill was constructed there between 619 and

621AD making it older than the previously earliest known tidal mill at

Little Island in Co. Cork which dates from about 630AD. The Cork mill is

a A twin flume horizontal-wheeled tide mill.As the name suggests tide mills or sea mills used the sea tides to fill an artificially created mill pond and when the tide receeded the enenrgy stored in the captured water was used to power the mill. Engineers estimate the mill wheels would probalby have been capable of developing between 7 and 8 horsepower.

Image: artists impression of a single flumed mill.

Thursday, April 11, 2013

Easter day and the foundation of western science

Predicting the date when Easter Sunday will fall is necessary when the church decided to place a 40 day fast in advance of it. Such an endeavour is not as easy as it may seem as it involves reconciling two irreconcilable calendars the lunar and solar. The month is named after the moon because each month is approximately the duration of a single moon cycle. The average number of days between moon phases is actually 29.5 days and months were devised to have 29 (hollow month) or 30 (full month) days. This Romulus calendar had only ten months with the spring equinox in the first month. It had only 304 days and it seems that the Roman just ignored the remaining 61 days which fell in winter. The calendar was reformed many times but it was not reliable. According to tradition under the second emperor of Rome Numa Pompilius c. 700BC two extra months were added (Januarius and Februarius) and this accounts for the mismatch in the month names Sept, Oct, Nov & Dec which translate as month numbers 7, 8, 9 & 10 but are now actually months 9, 10, 11 & 12. Confusion about when to add leap days meant that it was not till about 4AD that the Julian calendar had become reliable with leap days inserted every 4 years but it was still out of sync with the solar year by between 10 & 11 minutes. Thus the accumulation of this error over time meant that after about 131 years the calendar was out of sync with the equinoxes by one day. The date of the spring or vernal equinox is the basis from which the calculation of the date of Easter Sunday is taken. Thus errors in the calendar mean the calculation of Easter day may also be in error.

In 325AD the Council of Nicaea established that Easter would be held on the first Sunday after the first full moon occurring on or after the vernal equinox. Easter is based on the Jewish Passover which occurs on the first full moon after the vernal equinox by watching the phases of the moon the date of Passover can be determined easily a few weeks before. However the Christians had to know many weeks in advance when Easter Sunday was going to occur in order to calculate the date of Ash Wednesday. Mistakes in such calculations might mean that one parish could be celebrating Easter a week or two after their neighbours. Because fasting and abstinence was quite austere in medieval times the Easter celebration was anticipated like no other. If the neighbours got to celebrate first then they could legitimately celebrate it again in the next parish and it is fair to assume there would not be many happy Easter bunnies in a particular parish.

In order to accurately calculate the date of Easter Sunday it required figuring out how the universe worked.

“In fact, Ireland in the Early Middle Ages led the way in terms of serious scientific engagement with the physical universe and the attempt to understand the nature of the created world. The famous studies of Archbishop James Ussher in the seventeenth century have their antecedents in the efforts of Irish scholars, 1000 years before him, to offer rational explanations of the natural phenomena that they observed around them in their everyday world. More than anywhere else in Europe at that time, the Irish in the seventh century succeeded in figuring out ‘how things worked’ in the universe. They did so not only in the field of technical chronology (in which they were THE masters), but also in those areas of study that the modern world calls Science.” From Saints, scholars and science in early medieval Ireland – Prof. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, NUI Galway

Thursday, January 10, 2013

Prince John in Ireland

In the early 1180s Hugh de Lacy, lord of Mide (Meath) (who had recently married King Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair’s daughter) intended to make himself king in Ireland and it caused such alarm among the Norman rulers of England that they urgently d

ecided to send prince John to Ireland. In the winter of 1184-1185, Lacy was recalled and Archbishop John Cumin of Dublin was sent ahead to prepare the way. The annals record for 1185 that "the son of the king of England came to Ireland with sixty ships to assume its kingship," and Howden writes that, at Windsor on March 31, Henry "dubbed his son John a knight, and immediately afterwards sent him to Ireland, appointing him king," while the Chester annals record that John "started for Ireland, to be crowned king there." He did not, however, possess a crown as Pope Lucius III refused Henry’s request and it was only late in 1185 that his successor, Urban III, "confirmed it by his bull, and as proof of his assent and confirmation, sent him a crown made of peacocks’ feathers, embroidered with gold." By this point, however, John had returned from Ireland in ignominy and the crown was never worn.

Apart from being ill-behaved and ill-advised, the expedition was undoubtedly spoiled by de Lacy, the annals observing that John "returned to his father complaining of Hugh de Lacy, who controlled Ireland for the king of England before his arrival, and did not allow the Irish kings to send him tribute or hostages."

Image: King John's Castle in Limerick. John never visited Limerick but the castle was built on his orders and was completed around 1200.

Apart from being ill-behaved and ill-advised, the expedition was undoubtedly spoiled by de Lacy, the annals observing that John "returned to his father complaining of Hugh de Lacy, who controlled Ireland for the king of England before his arrival, and did not allow the Irish kings to send him tribute or hostages."

Image: King John's Castle in Limerick. John never visited Limerick but the castle was built on his orders and was completed around 1200.

Tuesday, January 1, 2013

The Annals of the Four Masters

The Annals of the Four Masters are mainly a compilation of earlier annals, although there is some original work. They were compiled between 1632 and 1636 in the Franciscan friary in Donegal Town. The entries for the twelfth century and befo

re are sourced from medieval annals of the community. The later entries come from the records of the Irish aristocracy (such as the Annals of Ulster) and the seventeenth-century entries are based on personal recollection and observation. The annals are written in Irish.

The chief compiler of the annals was Mícheál Ó Cléirigh, who was assisted by, among others, Cú Choigcríche Ó Cléirigh, Fearfeasa Ó Maol Chonaire and Peregrine Ó Duibhgeannain. Although only one of the authors, Mícheál Ó Cléirigh, was a Franciscan friar, they became known as 'The Four Friars' or in the original Irish, Na Ceithre Máistrí. The Anglicized version of this was "The Four Masters", the name that became associated with the annals themselves. The patron of the project was Fearghal Ó Gadhra, a lord in County Sligo.

Several manuscript copies are held at Trinity College Dublin, the Royal Irish Academy, University College Dublin and the National Library of Ireland. The annals have also been digitised and are available free from the website of University College Cork. http://www.ucc.ie/celt/publishd.html

Image: Signature page from the Annals of the Four Masters

The chief compiler of the annals was Mícheál Ó Cléirigh, who was assisted by, among others, Cú Choigcríche Ó Cléirigh, Fearfeasa Ó Maol Chonaire and Peregrine Ó Duibhgeannain. Although only one of the authors, Mícheál Ó Cléirigh, was a Franciscan friar, they became known as 'The Four Friars' or in the original Irish, Na Ceithre Máistrí. The Anglicized version of this was "The Four Masters", the name that became associated with the annals themselves. The patron of the project was Fearghal Ó Gadhra, a lord in County Sligo.

Several manuscript copies are held at Trinity College Dublin, the Royal Irish Academy, University College Dublin and the National Library of Ireland. The annals have also been digitised and are available free from the website of University College Cork. http://www.ucc.ie/celt/publishd.html

Image: Signature page from the Annals of the Four Masters

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)